Kaipimikanchik (Aqui estamos)

For decades, Kichwa communities who migrated to the United States from various parts of Ecuador have innovated and spearheaded different forms of artistic expression around the nation. Since the 1980’s, ‘Mindalaes’ formed by artists, merchants, musicians, dancers, etc. have founded systems of trade and market across territories as a way of economic survival, resulting in powerful footprints that have changed and raised the presence of Kichwa communities all over the world. However, if you were to ask any ‘Mindalae’ about these processes, especially during this pandemic, I wonder if we’d recognize this work as powerful at all. Maybe, at the cost of shaking up all the feels, I say I will always hold a bitter place for the powers who forced us out, and forced us into this way of survival.

There is a still ache that resurfaces in the indigenous Kichwa migrant community during the holiday season. The “algun dia mija…” (some day, mija), followed by the vibrant daydreams of rekindling connections with families in our territories—these are the winter songs I’ve grown up with since we migrated.

Sometimes I wonder how much of our innovation is a direct response to the violence of immigration. Pre-pandemic, our communities fiercely adapted, curated, and developed ceremonies and celebrations in direct connection with our communities of origin, in places that are quick to remind us that we ‘don’t belong.’ My mom curates an altar every new year cycle to pass on stories and memories. But recently she has started to include her own adaptations. One year, I remember she included all our immigration paperwork and pictures of all our family members together, you know, just in case.

Accommodating spaces to fit our current social contexts has been a method to keep protecting our culture, identity, and energies. Now during the pandemic, the same work continues as we see young generations fiercely taking up space in different multimedia platforms. It’s important to note that this work is originating in areas where economic access continues to be robbed and denied.

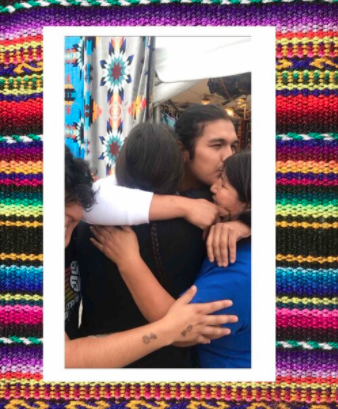

I close my eyes and my parents kiss my forehead as they head out to drive their feria van out of state this winter. Our small businesses have been tragically devastated due to capitalism and the pandemic, and many families who do not qualify for government aid are cut off from those lines of support. For many, that means being pressured to work in spaces/jobs that incentivize behaviors conducive to the spread of the virus. I think this pandemic has felt like an awakening to some, but to indigenous migrant workers, it has been a reminder to continue to strengthen our ‘Ayllu’-systems of defending and protecting each other. Because social distancing feels too familiar, it’s the way we’ve been treated—pushed aside because migrant labor has been immediately labeled as essential yet carries on failing to be protected as such every holiday season.